Medical Language Translation

Learning medical terminology

Leaning medical terminology is much easier when you translate the Latin into your native language. The bizarre words employed for anatomy and physiology are in fact simple descriptive expressions. It is difficult to recognize their meaning in Latin if you have never studies Latin.

However, once you translate anatomical names into your own language, the descriptions they represent will help you remember the body parts that they label. The human mind learns by associating new information with something already in memory, something familiar. The only exceptions in human anatomy are those items named after the person who first discovered them. International forums that come to a consensus periodically on medical terminology are beginning to rename anatomy previously named for its discoverer.

Scholarly language

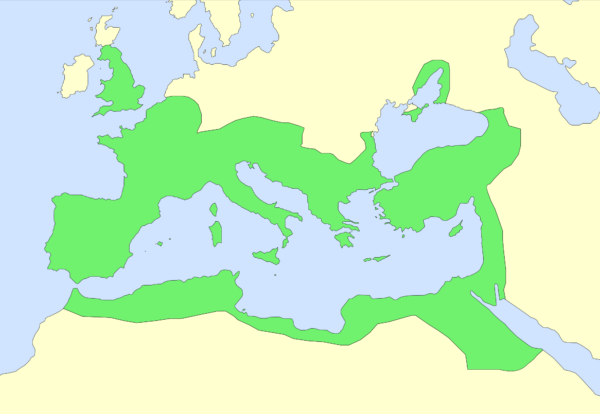

Why was medical terminology written in the scholarly language of Classical Latin and why are some of the words Greek? The answer is because Classical Latin was the universal language of the Western Europeans who wrote the first anatomy books.

Latin began as the language of ancient Rome. But it used the even older Greek alphabet. Latin developed from the Etruscan language. Etruscan was spoken in what is now the northern part of Italy in about 700 BC. It was the Etruscan language that incorporated words of the Greek traders who were active in the area.

Over time, spoken Latin deviated from the original form of the language in ancient Rome. Spoken Latin diverged into the romance languages, Italian, French, and Spanish between the 6th and 9th century. By the time of the late Roman Empire, another cultured form of Latin emerged from the speech of the educated. It is called Classical Latin.

Classical Latin was used as the universal language of scholars and the Catholic Church well into the 18th century. Human anatomy is considered an old science and dates to ancient Egypt. But, much of the human anatomic terminology studied by students today was invented during the 16th and 17th century. Because anatomic names had meaning in an old language, they will also have meaning in your language.

Medical language is descriptive

Surgeons who created medical language made up composite names to describe objects they were seeing for the first time. The composite names included a Latin or Greek root word with a Latin or Greek prefix and suffix. They translate like small sentences.

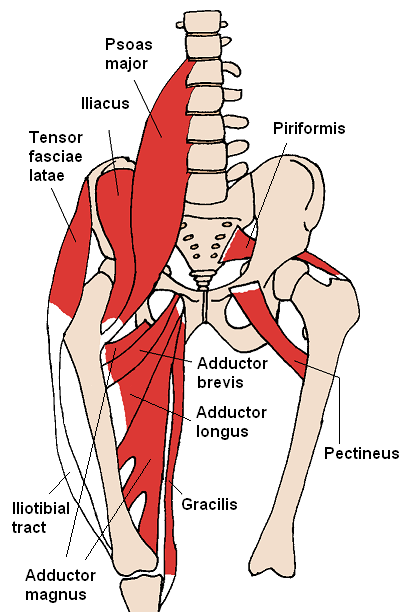

Because the evolution of the English language was also greatly influenced by Latin, the meaning of many anatomical names can be found in a college English dictionary. For example, the ‘Gracilis’ muscle of the thigh, was named using the Latin word from which the English adjective ‘gracile’ is derived. Gracile is defined in English to mean ‘gracefully slender’. And, the Gracilis muscle is a long, slender muscle as portrayed in the image below.

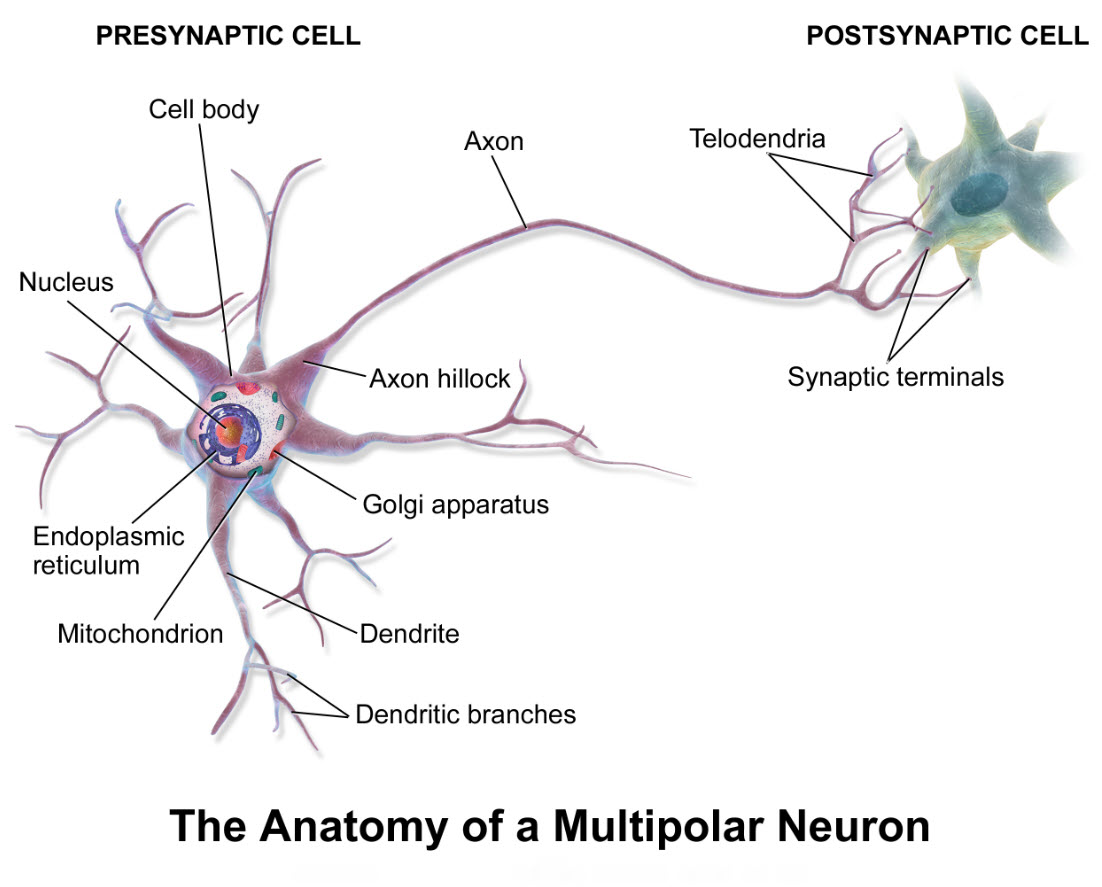

Another example is the brain cell called a neuron. Neuron originates from a Greek word meaning sinew or string. And string-like is a good description of the shape of a neuron.

The process of neuroplasticity is a hot topic in neuroscience right now. Here two descriptive words of Greek and Latin origin, neuron and plasticity, are combined. Plasticity originates from two similar words one Greek, the other Latin that mean to mold. So, neuroplasticity names an activity in the brain where string like cells are molded into a new anatomical shape.

Try to find the descriptive meaning of the labels in the artist’s illustration below. Hint: One of the anatomical structures shown is only named for the person who first discovered it. It will soon have a different name in textbooks.

Learning a language

Data suggest that adults have difficulty learning a language that is new to them in part because of the neural connections made in their brain’s language centers during infancy. We all learn our native language during infancy by hearing it spoken.

Up until about age 6 months infants can distinguish all the sounds used by all of the world’s languages. By age 12 months, infants’ brain pathways begin to adapt and support concentration on only the sounds of the language spoken around them.

Adults wanting to learn the words of a different language need to do more than just read them. Learning new words by listening is instinctive for the human brain while reading is a skill that must be learned. Recent studies in college science education have experimented with new approaches to teaching scientific words by combining an auditory component with reading.

Educators found that reading a new and difficult scientific word out loud three to five times each day for several days improved students’ ability to remember the word, to spell it correctly, and to better absorb printed material that used the word. Adding auditory input to reading of scientific words was significantly more effective in creating word memory than reading alone.

I would suggest going a step further. If English is not your first language and you have not studied Classical Latin or Greek, you may want to translate scientific words into your native language first. This will connect the sounds of the foreign scientific words to the sounds of your own language.

Medical language translation

Google has a great free resource where you can put this strategy to work. You can find it by clicking here. Start with the muscles of the leg and thigh. Begin by typing some muscle with a strange sounding name in the first box, and then have the program translate that into your native language. Then click on the microphone beneath each version of the word and listen. After the computer pronounces the word you should also pronounce it in both languages.

Repeat this process several times to allow your brain to map the meaning of the word to the familiar sounds of your native language. Then when you come across the word in your reading again pronounce it out loud. You might also try doing this with the labels on the illustration above of a neuron.

Try it! If you can pronounce an anatomic name and understand its meaning, it will be much easier at test time to recall the right name and its spelling. You will not mix parts of several descriptive names to make a new name that will lose points. You will find that learning medical terminology is easier than you thought.

Further Reading:

Repetition in Anatomical Names

Muscle Names Have Meaning, Keving Patton Video

Memory, Patterns, and Themes in Anatomy & Physiology

Do you have questions?

Send me an email with your questions at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com or put them in the comment box. I always read my mail and answer it. Please share this article with your fellow students taking anatomy and physiology by clicking your favorite social media button.

Margaret Thompson Reece PhD, physiologist, former Senior Scientist and Laboratory Director at academic medical centers in California, New York and Massachusetts is now Manager at Reece Biomedical Consulting LLC.

She taught physiology for over 30 years to undergraduate and graduate students, at two- and four-year colleges, in the classroom and in the research laboratory. Her books “Physiology: Custom-Designed Chemistry”, “Inside the Closed World of the Brain”, and her online course “30-Day Challenge: Craft Your Plan for Learning Physiology”, and “Busy Student’s Anatomy & Physiology Study Journal” are created for those planning a career in healthcare. More about her books is available at https://www.amazon.com/author/margaretreece. You may contact Dr. Reece at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com, or on LinkedIn.

Dr. Reece offers a free 30 minute “how-to-get-started” phone conference to students struggling with human anatomy and physiology. Schedule an appointment by email at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com.

Comments

Medical Language Translation — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>