Direction in anatomy

Today human anatomy is regarded as being a complete science. The “what is where” of the human body is largely known. But remember as you struggle to learn anatomical names and location of body parts that it took about 3600 years to make it as ‘complete’ a science as it is.

There is still individual and age variation in human body structure to be considered. And anatomists are still working out the brain’s cellular anatomy.

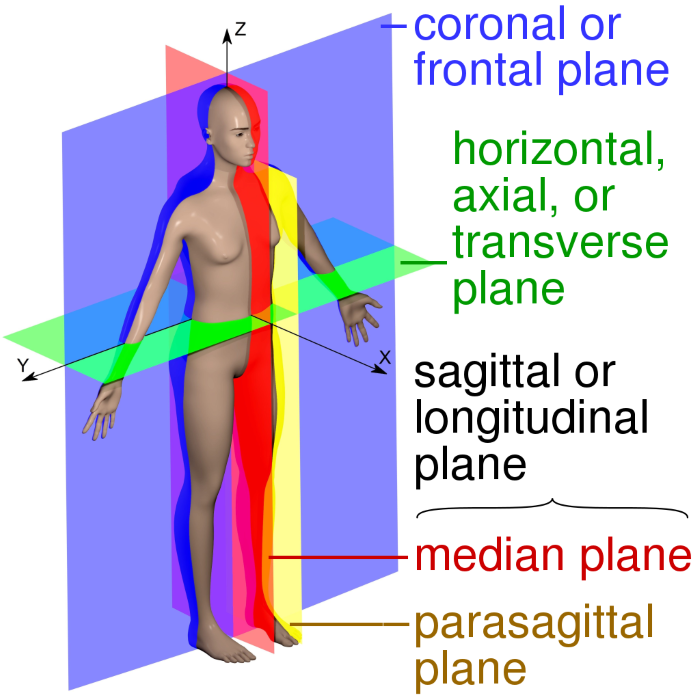

Ancient anatomists describing mobile structures needed reference points upon which to base their description of “what is where”.

A uniform description of three-dimensional anatomic orientation was devised in early studies, and it was largely kept and expanded upon. It is easier to communicate when everyone uses the same words.

Human anatomic position

A first issue to arise in naming human parts was the number of positions that flexible human bodies can acquire. A single position was needed that could be used as a reference for describing where the pieces were relative to each other.

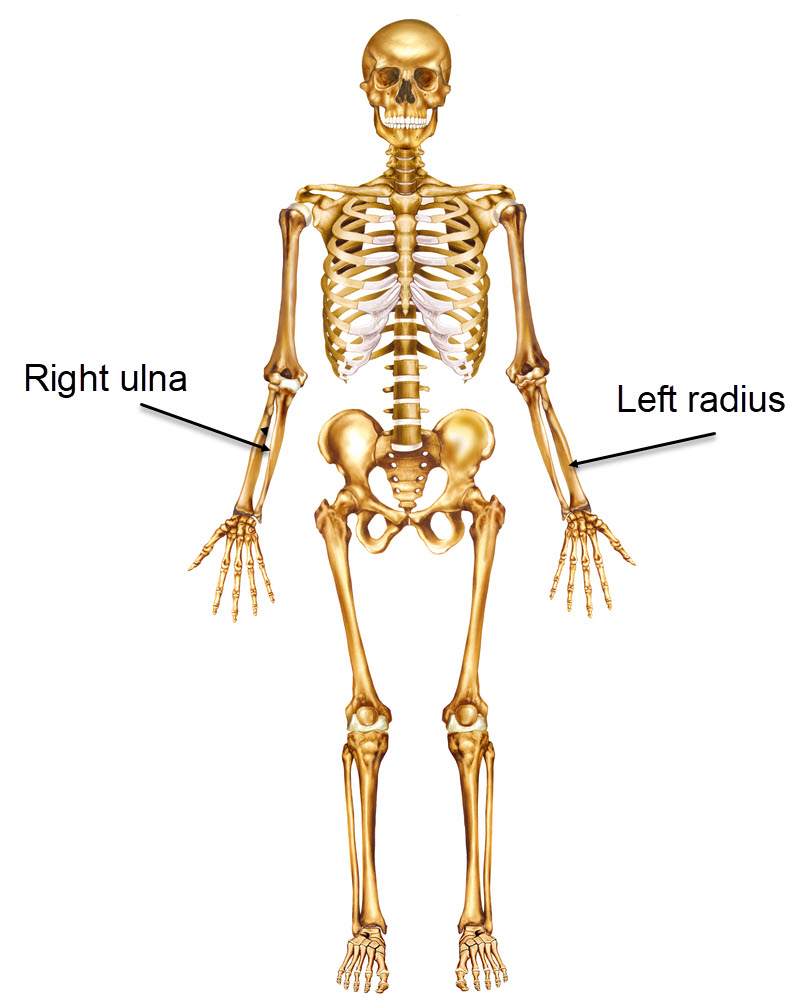

That single position became known as the human anatomical position and is displayed by this skeleton. No matter what position a cadaver assumed, all descriptions were extrapolated back to where the body part would be in the anatomical position.

It takes a bit of imagination and focus to transfer what you are looking at into the anatomical position of another person. That is, a standing person, head and eyes facing forward, feet together, arms to side, palms of hands facing forward.

The directional term lateral is used as a modifier for both sides of the body, left lateral and right lateral. As opposed to lateral, the term median is used to define a point in the center of the organism. The word medial used as a descriptive means toward the median plane of the person.

In the anatomic position, palms forward, the radius bone lies lateral, and the ulna bone is medial. With rotation of the forearm as the palms turn toward the back, the radius moves to a medial position and the ulna is then lateral.

Bilateral symmetry

Humans are said to have bilateral symmetry. That means the halves of the body formed by a theoretical median plane, shown below in red, divides the body into two parts. that are mirror images of each other.

Media plane of the human body shown in red, David Richfield and Mikael Häggström, M.D. and cmglee, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Human hands shown below illustrate human bilateral symmetry. The symmetry applies only to the body’s shape, not to its internal organ structure.

Who’s right and left?

Problems with assessing right and left arise if you do not remember that for a person you are facing right and left may be reversed. Only if both of you are facing the same direction do right and left align.

To get answers correct on anatomy practical exams, it is identification of the right and left body part that is important. Some of us become confused with the issue of right and left, because we are so accustomed to mirror images of ourselves.

It is easy to forget that our mirror image is the reverse of our real self. Some people are uncomfortable with pictures of themselves because a picture is not their mirror image.

The fire truck pictured below displays an awareness of the importance of the mirror image of a written sign. Notice the word ‘FIRE’ is written forward for oncoming traffic, and backward in its mirror image for drivers who see it in their car’s mirrors.

Labeling on fire truck written for visual and mirror viewing, Public Domain image, Wiki Media Commons

Position of appendages

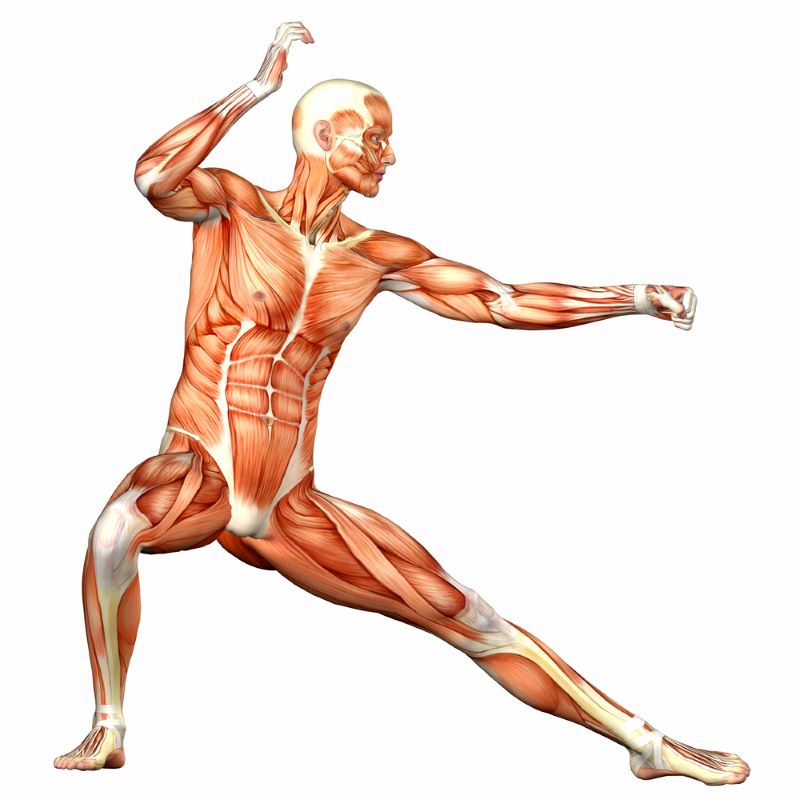

Appendages, arms, legs, and pelvis require another set of directional terms to describe their position relative to the torso. One of the terms, proximal describes the point where the appendage joins the torso. The other term, distal is used for the point farthest from the place of attachment of the appendage to the torso.

Practice locating body parts as proximal or distal with the help of this illustration, Chastity Q, Shutterstock.com

Proximal and distal are often used as relative terms. For example, the elbow (shown above) is proximal to the hand . . .the elbow is closer to where the arm attaches to the torso than the hand is. But the elbow is distal to the shoulder . . .the elbow is in a position further away from the torso than the shoulder joint.

More human orientation descriptors

In the scheme of other human orientation descriptors, anterior is toward the front while posterior is toward the back. Superior is toward the head. The opposite term, inferior, is a relative descriptor generally used to mean below some other body part.

Internal body organs are described as superficial meaning near the body surface, or deep meaning internal and away from the surface.

To summarize

In most anatomy courses these human body orientation descriptors are learned early in the instruction. They are learned in isolation. Because anatomy descriptors appear easy you may not want to focus much of your precious time studying them. It all seems so obvious that it is natural to think, “I know that”.

Orientation descriptors are not used a lot until your instructor hands out long lists of muscles, nerves, and blood vessels to be learned. By then your memory of orientation descriptors may be lost in the fog of too many facts accumulated since the descriptors were last learned.

The trick is to avoid blowing off these terms early in your study of anatomy. Make friends with them instead. Practice describing all body structures you learn with these descriptors. It may feel strange at first but sticking with it will pay off.

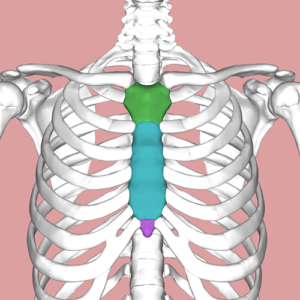

For example, when learning bones, you can decide whether the human sternum (colored set of bones) is located anterior or posterior, inferior, or superior to the pelvis, medial or right lateral or left lateral when the body is in the anatomic position. In doing this, you will remember why you do not use the terms proximal and distal to locate the sternum.

Do this, and when it comes time to learn names and locations of muscles, nerves, blood vessels you will be way ahead of your classmates.

There is a comment box below where I hope you will tell me if knowing the logic behind anatomical descriptions of orientation helps you remember and use them properly. Please share this article with your classmates by clicking on one of th social media icons on this page.

Also, I would like your help in choosing other topics for future articles. Please tell me what areas of anatomy you find the most frustrating.

Further Reading

Do you have questions?

Please put your questions in the comment box or send them to me by email at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com. I read and reply to all comments and email.

If you find this article interesting share it with your fellow students or send it to your favorite social media site by clicking on one of the social media buttons on the page.

Margaret Thompson Reece PhD, physiologist, former Senior Scientist and Laboratory Director at academic medical centers in California, New York and Massachusetts is now Manager at Reece Biomedical Consulting LLC.

She taught physiology for over 30 years to undergraduate and graduate students, at two- and four-year colleges, in the classroom and in the research laboratory. Her books “Physiology: Custom-Designed Chemistry”, “Inside the Closed World of the Brain”, and her online course “30-Day Challenge: Craft Your Plan for Learning Physiology”, and “Busy Student’s Anatomy & Physiology Study Journal” are created for those planning a career in healthcare. More about her books is available at https://www.amazon.com/author/margaretreece. You may contact Dr. Reece at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com, or on LinkedIn.

Dr. Reece offers a free 30 minute “how-to-get-started” phone conference to students struggling with human anatomy and physiology. Schedule an appointment by email at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com.

I’ve always found this very confusing. I thought with the brain the left hemisphere would be on the right with the anatomical position, but is that wrong based on the above description? When it comes to reading various things I’m never really sure from what point of view or position in space/on the body it’s in reference to.

Do you happen to recommend any books?

Hello Chris, The problem you are having with right and left is a very common one for students. It helps to put yourself in the anatomic position for comparison. For example, if you are learning an articulated human skeleton, stand behind the skeleton to determine its right and left. From behind your right and left match the skeleton’s right and left. It is only when two people in the anatomic position are facing each other that things seem reversed.

My name is Rosa .

I took Anatomy and Physiology and pass with a D and I decide to take it again. I study hard and when it come to my practical and test I get bad grades. I get frustrated and upset because I study so hard and I don’t know what I’m doing wrong I’m thinking to drop the class . I don’t want another D . I want to pass with A . What is your suggestion please help me what should I do .

Hi Rosa, I think you are asking about lab practical exams, but you must be having problems in lecture as well. I think you must be taking first semester A&P, but the topics for each semester vary by school. Send me an email at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com and we can talk more about your specific problems with the material.

Why does people tell you that A&P is so difficult to pass?

I am told that the anatomic names are hard to memorize because they are unfamiliar words. I way around that problem is to get out the dictionary and find the root words’ meaning in your native language. For example part of neuron is its dendrites. The word dendrite translates from Latin into ‘tree’. And, neuron dendrites look like branches on a tree. Physiology is a different problem. In A&P courses it is taught in the same sequence as the anatomy, and it is hard for students to see the whole of it when it is broken up into such small pieces.

Im having trouble uderstanding this question to find the answer.

“Why do you need to know body orientations and direction when talking about the human body?

Because muscle names often include the direction of the movement they elicit in their name. Direction needs a common starting point for the names to make sense.

Science has never been my forte’ even from elementary school until present it has always been a challenge for me. Need suggestion for better study habits and better grades.

Hi Joyce, My suggestion is to first work with the language of the science. Much of science is in Latin, but Latin can be translated into modern languages. Next, do not try to learn it all. Focus on the ideas your instructor is emphasizing. If they do not make sense to you, be sure to go to your instructor’s office hours and ask. Try to get the big picture before you memorize disorganized details. Science course build on themselves, so keep looking back at the previous material to see how it supports the newer material in lecture. Most important of all is to find someone to talk to about what you are studying. The human brain remembers sound better than what it reads. Good luck. If you get stuck send me an email at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com and I will see if I can help.

what is the importance for anatomists to have a reference position

To describe where a particular body part is relative to other structures it was necessary for the early anatomists to have a starting point. The human body can assume many different positions. By changing the body’s position a the hand can be put over the head or under the foot. Most anatomic parts were named and described relative to a chosen position that your textbook calls the “anatomic position.”

I always thought it to be confusing and hard to understand. You make learning anatomy and physiology interesting, easy to understand and fun for me. I may have to change my major! I love how you present the data. I wish I could be your apprentice. Thank you and please keep posting.

Hello,

What is a way to determine if a bone is a “right or left”? I have some trouble determining that.

Almost all students struggle with right and left in anatomy, but it is important to get it correct. If you are facing another person, or an articulated skeleton, your right arm will be directly opposite the other person’s left arm. Right and left on two people are only in the same position if you are both facing the same direction as you stand. I hope this helps.