Article #1 of a 7 Part Series

Psychologists emphasize that words, even strange words, are learned quickly by the human brain when they are associated with something familiar. Thus, assigning meaning to the original Classical Latin names used for explaining the brain allows for visualization of the objects they represent and makes them far easier to remember.

Most of the bizarre, composite words employed describing brain function are in fact simple descriptive expressions. The good news is that Classical Latin can be translated into modern languages. OK, taking a course in Latin is not practical. There is an easier way to do this.

Language and Sound

Infants and young children acquire their primary language through their brain’s instinctive interpretation of auditory input. By simply hearing the subset of sounds spoken by another human, infants can sort the sounds of the speaker’s language into their proper order and map them to importance.

Adults trying to learn a second language find reading and writing a new language is not enough to develop fluency. Rather listening to the language over an extended period is required to build new language pathways in the brain to parallel those of the native language learned in infancy. The same holds true for learning scientific language.

Scientific language is further hindered by the stringing together of many individual words into pseudo sentences. The solution is to break the long words into their component parts and to find the meaning of each part. Then the parts must be rearranged into a sensible order. Word order is not the same in all languages.

To keep the parts of compound scientific names in proper order, speaking and listening must be included in the learning process.

Scientific Terminology

Recent studies at colleges experimented with approaches to helping students learn scientific terminology. Educators found reading a new and difficult word out loud three to five times improved students’ ability to remember the word, to spell it and to better absorb material using the word. Adding auditory input to reading of scientific words was more effective in creating word memory than reading alone.

There are online tools available for learning how to pronounce medical terminology. An example can be found at https://translate.google.com. At this site you can run a test with the word ‘neuron‘. Type the word neuron in the box labeled English. Below the box is an explanation of the meaning of neuron. Then pick a language for translation in the second box.

In each box there is the symbol of a microphone. Click on the microphones and listen to the pronunciation of neuron in a couple languages. Try saying neuron out loud several times in your favorite language. Notice the difference in the sound of the word neuron from language to language. This is because the letters of the alphabet do not represent the same sound in every language.

Neural Anatomy

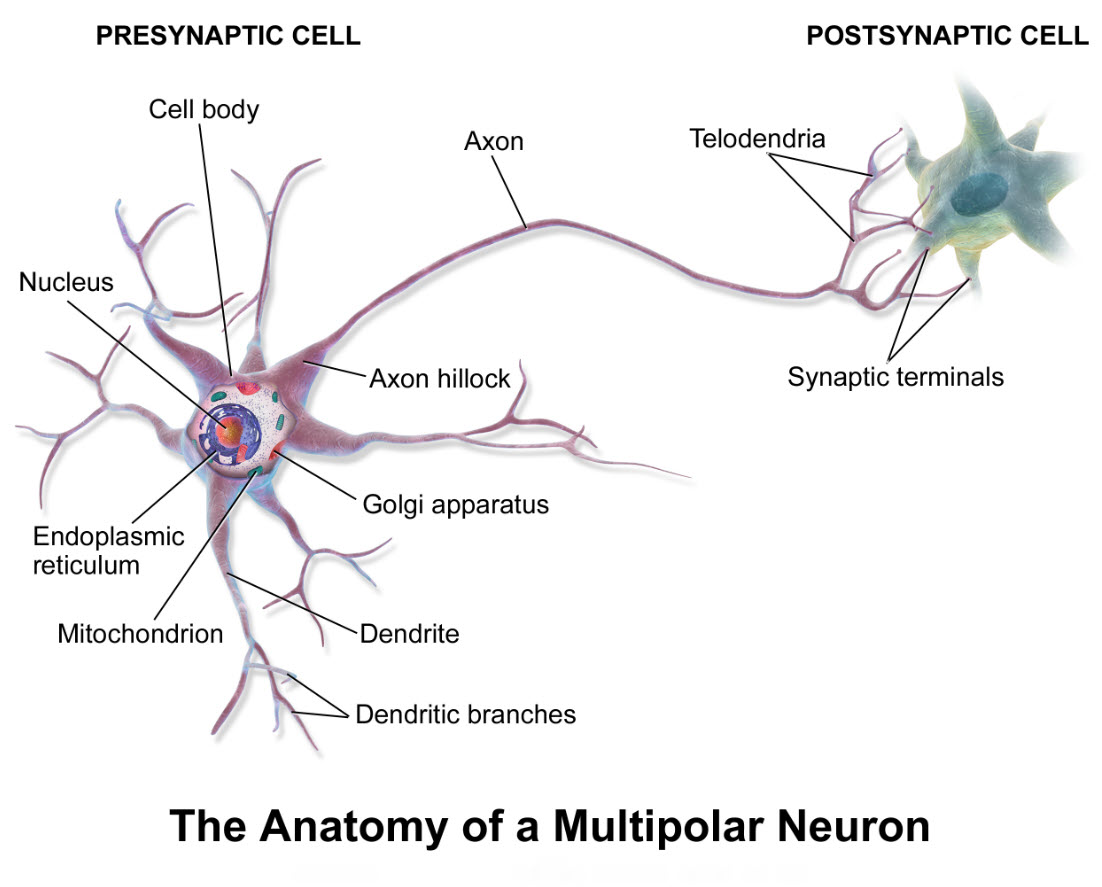

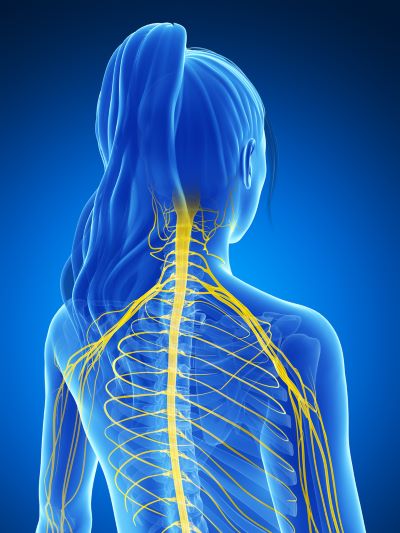

When studying neural anatomy, it is essential to distinguish among neuron, nerve cell and nerve. Nerve is often used as if it means the same as neuron or nerve cell. But that is incorrect. Both neuron and nerve cell refer to an individual electrical cell of the nervous system. In contrast, a nerve is a cable-like bundle. The bundle includes just the part of neuron called an axon.

The word axon comes from the Greek word for axis, a straight line. Classical Latin included features of Greek origin. Many neurons contribute their elongated axons to the nerves running throughout the body. Each axon in a nerve is part of a single neuron. Some brain neurons controlling contraction of skeletal muscles have axons several feet long.

Nerves are enclosed by a tough sheath of tissue. The word neuro, from the Greek language, means sinew or string. Nerves in fact look like white string when seen in living tissue.

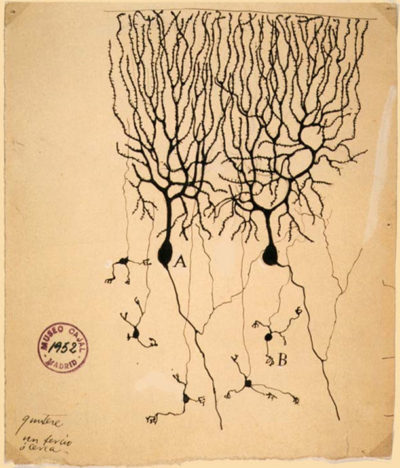

The individual cells of the nervous system, neurons, were not observed by scholars until long after nerves were described. Neurons of the brain were described for the first time near the end of the 1800s.

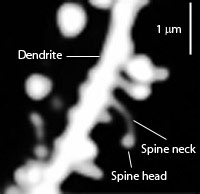

Another neuron functional part is its dendrite. A dendrite is a series of membrane projections that radiate from the cell body of a neuron.

Dendrites divide like branches of a tree. In Ramon y Cajal’s drawing, the dark central ovals are the neuron cell body. The elaborate branches above the cell body are the dendrites. Over 150 different types of neurons have been described based upon the shape of their dendrites. The name dendrite also originated in the Greek language from a word meaning tree.

An even smaller part of a neuron is the dendritic spine. Spine is a derivative of the Latin word spina meaning thorn like structure on a stem. If you look closely at Cajal’s drawing you can see that he included dendritic spines on the neuron dendrites. Each dendrite may display several thousand dendritic spines. Dendritic spines change their shape over time in response to factors in the local environment.

Such dynamic change in the character of dendritic spines is the physical component of what scientists call neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is one of those combined words. Plasticity originates from two similar words, one Greek and one Latin, describing the process to mold.

Many connections between neurons are where the axon terminal of the first neuron connects with the dendritic spines of the second. The neural anatomy of dendritic spines is associated with memory formation and building a language from listening to sounds.

Handy Resources

- Google translate is a lot of fun. The same word, same spelling is often pronounced very differently in various languages, because the letters of the alphabet vary in sound by language.

- Wikipedia offers a helpful list of Latin and Greek root words in English.

- The American Heritage College Dictionary published by Houghton Mifflin Company includes with the definition of its words the source language word and the meaning of the source.

Click Here for “A Glossary of Key Brain Terms”

Click Here for “A Glossary of Key Brain Terms”

Margaret Thompson Reece PhD, physiologist, former Senior Scientist and Laboratory Director at academic medical centers in California, New York and Massachusetts is now Manager at Reece Biomedical Consulting LLC.

She taught physiology for over 30 years to undergraduate and graduate students, at two- and four-year colleges, in the classroom and in the research laboratory. Her books “Physiology: Custom-Designed Chemistry”, “Inside the Closed World of the Brain”, and her online course “30-Day Challenge: Craft Your Plan for Learning Physiology”, and “Busy Student’s Anatomy & Physiology Study Journal” are created for those planning a career in healthcare. More about her books is available at https://www.amazon.com/author/margaretreece. You may contact Dr. Reece at DrReece@MedicalScienceNavigator.com, or on LinkedIn

Featured header image: ©Moonlight Photo Studio, via Shutterstock.com